Berkeley, California’s Japanese Anarchist Newspaper

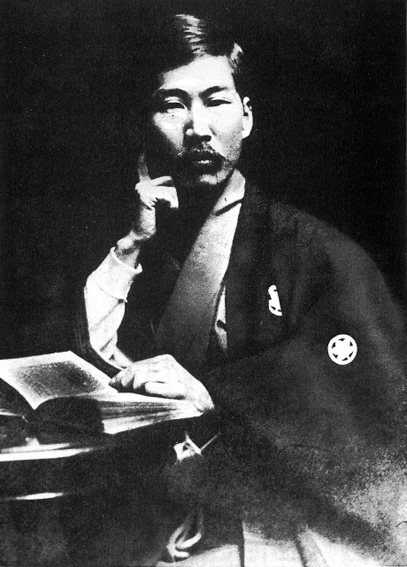

The San Francisco Bay Area was a central node in a globe-spanning, empire-challenging anarchist movement in the first years of the 20th century. Perhaps the most prominent Japanese anarchist during these years was journalist Kōtoku Shūsui. When Kōtoku’s set foot in San Francisco in November, 1905, his radical conscience had been developing for years. His 1901 book Imperialism: Monster of the Twentieth Century remains a seminal early condemnation of global imperialism. A couple years later he helped launch the Heimin Shinbun in Tokyo, a socialist anti-war daily newspaper. Kōtoku’s vocal opposition to the Russo-Japanese war in the pages of the Heimin Shinbun led to his imprisonment and the paper’s shuttering.

While incarcerated, Kōtoku struck up a correspondence with San Francisco-based Anarchist Albert Johnson. Upon release Kōtoku entered a short self-exile by crossing the Pacific to California. In California, Kōtoku’s contacts with the Industrial Workers of the World and experiences with grassroots mutual aid in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake made him a convinced anarchist.

Kōtoku also struck up a relationship with local Japanese migrants. A former colleague, Shigeki Oka, was involved in the local branch of the Heiminsha, the organization that had published the Heimin Shinbun. Before Kōtoku returned to Japan in June, 1906, he brought many of these new contacts together to form a Social Revolutionary Party. The initial membership counted 52 names, most from the nearby Bay area cities but also including contacts in Chicago, Boston, and New York.

The Social Revolutionary Party’s members soon launched a paper in Berkeley: Kakumei, or Revolution in English. Its first issue has been preserved in the University of California, Berkeley library and is now made available as a digitized copy. The first page of the eight-page paper contained English-language articles directed toward the broader radical movement, while the remainder was written in Japanese.

The English articles offered an introduction to the emerging Japanese Anarchist movement. As a solution the increasingly brutal poverty faced by many under capitalism, Kakumei clearly rejected “the trifiling legislation which the capitalist class may from time to time flink to the workers” as being “about as effective as the tiny stream from a baby’s water-gun thrown in a raging fire.” Instead, Kakumei clearly called for “the overthrow of Mikado, King, President as representing the Capitalist Class as soon as possible, and we do not hesitate as to the means.”1

The paper also spoke to the “ignorance of the white fellow workers as to the actual interests of the working class the world over.” 1907 was a high-point for racist exclusion movements in California. The mayor of San Francisco, Eugene Schmitz, was a Musician’s Union labor leader who was a prominent figure in the Japanese-Korean Exclusion League. That latter body would morph into the Asiatic Exclusion League in 1907, initiating branches in many white settler-colonial cities along the Pacific Rim. Kakumei argued that the economic troubles their “foolish white fellow workers” often blamed on Japanese laborers was in fact the fault of capital. The only solution was the classic motto, “Working Men of All Countries Unite!”2

Though Kakumei was ultimately short-lived, its contributors played a significant role in the trans-pacific anarchist movement of the years to follow. Tetsugoro Takeuchi, who had written an article suggesting the American president might be assassinated, was forced to move to Fresno. There he helped organize thousands of farmworkers into the Japanese Fresno Federation of Labor. Five thousand of them struck in 1908 with the support of Italian and Mexican IWW members. Takeguchi also published Rodo (Labor) as the organ of the Japanese Fresno Federation of Labor. Another founding member of the Social Revolutionary Party was Iwasa Sakutarō, who became a lifelong anarchist-communist until his death in 1967.

Further Reading

The Proletarian: digitized Japanese-English bilingual IWW paper 1909-1910

Stafan Anarkowic, Against the God Emperor: The Anarchist Treason Trials in Japan

Masayo Umezawa Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920

Robert Thomas Tierney, Monster of the Twentieth Century: Kōtoku Shūsui and Japan’s First Imperialist Movement

Kenyon Zimmer, Immigrants Against the State: Yiddish and Italian Anarchism in America

1“The Japanese-Socialist Movement in California,” Kakumei, December 20, 1906.

2The President and Japanese Exclusion,” Kakumei, December 20, 1906.