San Francisco Anarchist Newspaper

Title _ Vol.-No. _ Month-Day-Year

- Beacon_1-12_4-26-1890

- Beacon_1-13_5-3-1890

- Beacon_1-15_5-17-1890

- Beacon_1-16_5-24-1890

- Beacon_1-17_5-31-1890

- Beacon_2-1_1-31-1891

- Beacon_2-2_2-7-1891

- Beacon_2-6_3-14-1891

- Beacon_2-7_3-21-1891

- Beacon_2-8_3-28-1891

- Beacon_2-18_7-25-1891

The years 1886 and 1901 are rather well-known to students of anarchism in so-called North America. The former witnessed a continent-spanning labor upheaval, most famously associated with the May Day mythology of the Chicago Haymarket. The latter saw U.S. president William McKinley assassinated by Michigan-born anarchist Leon Czolgosz. These events brought about severe repression of anarchists. Yet in both cases, anarchism persisted. Despite the separate treatments these events generally receive in histories, threads of continuity spanned that decade-and-a-half.

The decentralized nature of anarchistic movements often fosters historical misunderstanding. Repression and the associated disappearance of a well-known group or periodical has sometimes been taken as shorthand by historians for the ‘death of anarchism’ in some particular time or place. Human continuities with later manifestations are frequently difficult for later observers to track. But stepping beyond confined geography and thinking like the loose network that was and is anarchism clarifies such connections.

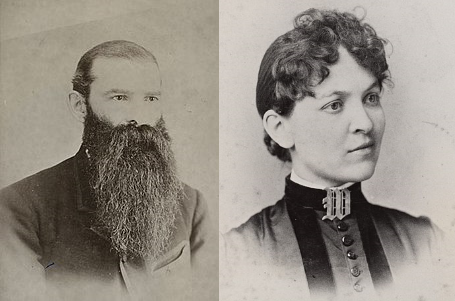

One vital bridge connecting the anarchisms of 1886 with those of 1901 is the The Beacon. This newspaper was started by one Sigismund Danielewicz in San Diego in 1889 before moving to San Francisco the next year. It survived only until 1891, taking on Clara Dixon Davidson as a new editor for its final issues. During its short life and frequent disruptions, The Beacon filled a vital vacuum in a militant emerging English-language movement. This blog brings eleven issues of The Beacon to digital life for the first time.

A key predecessor of The Beacon was the The Alarm, edited by Albert Parsons in Chicago. That weekly paper helped foster a widespread radical network seeking to tear down existing systems of domination by any means necessary. Bold words favoring newly invented dynamite made the paper especially infamous among the powerful. The Alarm reached beyond Chicago; many subscribers were women and men in small towns and cities who enthusiastically engaged with its ideas.

Albert Parsons was hanged by the state in late 1887, one of several Anarchists scapegoated for the explosive deaths of a number of assaultive Chicago police. Just before his murder, The Alarm was revived by a local collaborator, Dyer D. Lum. While this second Alarm helped bring together the network fostered by the first, it was short-lived and after moving to New York reputedly took a more moderate stance. These same years witnessed a new prominence for ‘philosophical anarchists’ who claimed to appreciate the social ideals of anarchism while rejecting militant (or sometimes any) means of achieving them.

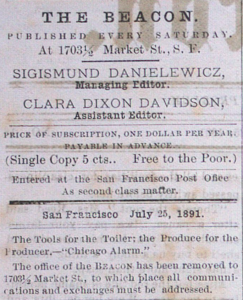

In San Francisco, Sigismund Danielewicz oriented The Beacon towards continuing the spirit of the old Alarm. The Beacon’s second volume made this intention clear by adding the Alarm’s famous subtitle to its own masthead: “The Tools for the Toiler; the Produce for the Producer.” Between poems and short anarchist stories lie compelling calls for the sort of dynamite insurrection that even a few readers complained ought to have died with the Haymarket martyrs.1

A handful of available issues remain of his 1889-1891 paper The Beacon.2 During Danielewicz’s tenure as editor, the paper frequently expressed solidarity with anarchistic free love journals facing censorship, but also argued that mere “agitation” might not be enough to free the jailed editors.3 Space was given for advocates of “Passive Resistance” but Danielewicz inserted his rebuttals when he had the space.4 In its later run, frequent contributor Clara Dixon Davidson joined Danielewicz as assistant-editor, holding more of an ‘evolutionary anarchist’ perspective in contrast to Danielewicz’s advocacy of ‘physical force revolution.’ Danielewicz apparently handed her the reigns entirely near the end of the paper’s life.5

The Beacon was always run on a limited budget; on multiple occasions it had to suspend publication until more funds could be found. Danielewicz’s tendency to give away numerous free copies certainly didn’t assist financial matters, even if it helped to spread the paper’s message. In addition to taking the common newspaper side-hustle of offering paid job-printing, small operations located at The Beacon‘s office helped fund the presses. Danielewicz had a long career as a barber, and offered cuts at The Beacon barbership to support the paper, also offering to sharpen hair clippers. The office was also home to a laundry.

Old contributors to The Alarm found ample space for their ideas in The Beacon. Dyer D. Lum frequently contributed think-pieces on the nature of anarchism.6 Lucy Parsons spoke up in the pages of The Beacon to defend its radical line.7 Even new Chicago anarchists awoken by the events of Haymarket turned to The Beacon for a time. Voltairine de Cleyre, for instance, published poetry in its pages.8

Lesser known members of The Alarm circle also turned to The Beacon. Dr. Mary Herman Aikin of Grinnell, Iowa was an enthusiastic supporter.9 She thought the The Beacon would better reach “the men who go at night to miserable shelter and wretched food, after long hours of toil” than other Anarchist papers with “fine-spun theories” like Twentieth Century and Denver’s Individualist. The Beacon was “not afraid to declare that it means war to existing social conditions.” Aikin supposedly earlier helped organize a local “group of some ten or eleven persons” in her town affiliated with the Black International. She also ran a medical practice favorable to the poor and apparently performed abortions for women who requested them, illegal in Iowa since 1873. A nearly 70 year old Mary Herman Aikin was indicted for an abortion in 1898 and died in prison four years later.10

Importantly, The Beacon also linked those better-developed networks in the US-Midwest and East with Danielwicz’s own connections on the West Coast. While the ‘Black International’ played a key role in the upheavals of 1885-86, a more ignomious counterpart was forming in the West. San Francisco was home to a ‘Red International,’ the International Workmen’s Association, formed in late-1882 by radicals associated with deeply-racist local labor and socialist movements. Danielewicz served as the Secretary of this body while it spread as far as Seattle, Washington and Topeka, Kansas.

These ‘Red’ and ‘Black’ Internationals enjoyed a messy relationship through the events of ‘Harmarket,’ sometimes discussing a merger, at other times differing wildly on matters of organization and principal. The most common objection by ‘Black’ Internationalists to their Western counterparts was also the issue that drove Danielewicz to leave: the Western IWA’s lead role in a horrific wave of 1885-1886 anti-Chinese pogroms.11

![Logo with a glove topped by a mason's toop and a phyrgian cap, with International Workmen's Association [The Red]' below](https://historicalseditions.noblogs.org/files/2022/04/IWA-Truth-Logo-300x194.png)

Those who stuck to this racist line would continue the ‘Red IWA’ for a few more years, parlaying their racist drive into the institutional foundations still utilized by AFL-CIO labor organizations in the Western US. When Danielewicz opposed these actions at a key convention, he virtually stood alone in the organization. Yet when he departed soon afterwards, he held on to a handful of connections in the West, and along with these built a stronger relationship with anarchists further-afield. By the time those comrades had need of an outlet, Danielewicz’s Beacon was ready to oblige.

One key connection was Henry Addis of Portland, Oregon whose first known anarchistic writings appeared in The Beacon. Just a few years later, Addis joined with Mary and Abe Isaak and a handful of others to found The Firebrand.12 Facing state-repression related to oppressive ‘obscenity’ laws, the Firebrand collective dispersed in two directions. Some helped form the Home anarchist colony near Tacoma, Washington, while others launched a new 1896 Anarchist paper in San Francisco: Free Society. Danielewicz himself became a frequent Free Society contributor for some time. Free Society is also well-known for inspiring the 1901 actions of Leon Czolgosz, illustrating the anarchistic through-lines that ran through The Beacon. Free Society would be followed in spirit by Emma Goldman’s famous Mother Earth.

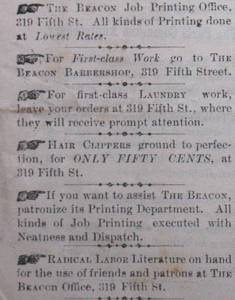

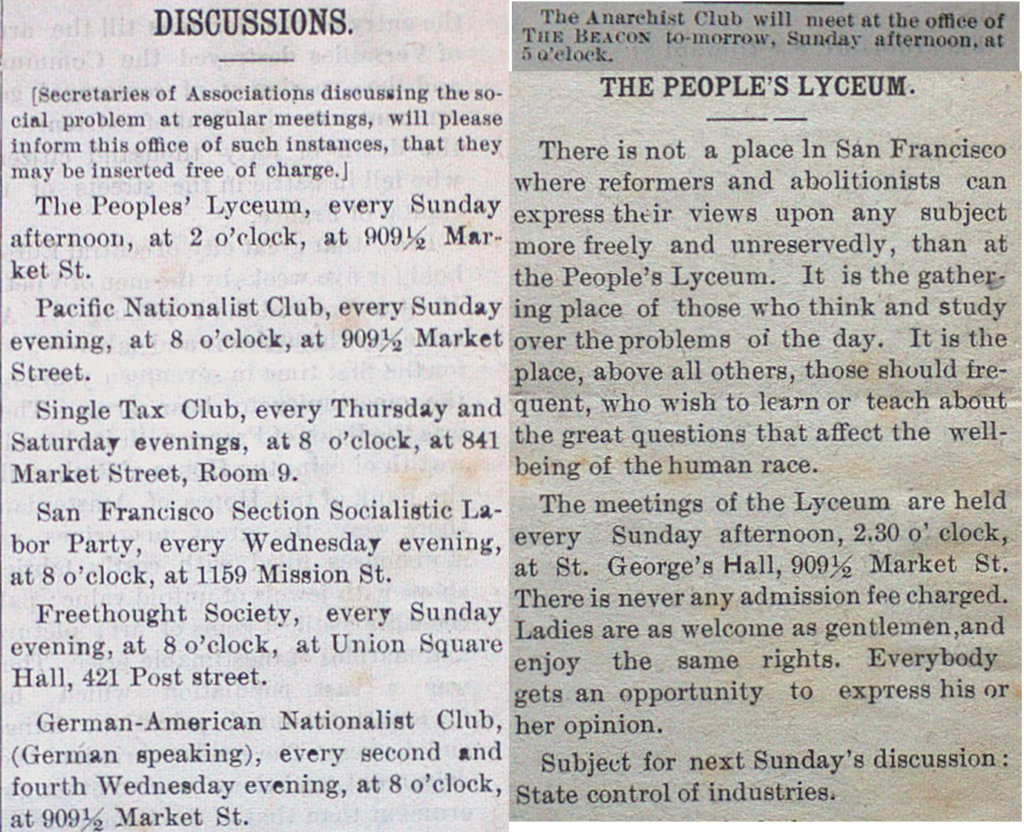

The Beacon also served a local role, giving a platform to a few of San Francisco’s budding anarchist and other radical groups. An ‘Anarchist Club’ met for some time on Sunday afternoons at The Beacon‘s offices. The Beacon‘s editors were also active participants in the local ‘People’s Lyceum,’ a radical discussion circle. Local associations ‘discussing the social question’ were offered free listing in the Paper. The listings also included, among others, groups aligned with Henry George’s ‘Single Tax’ movement, The Socialist Labor Party, and Edward Bellamy’s ‘Nationalist’ state-socialist movement.

The Beacon was even known overseas, prompting inquiries for copies from ubiquitous anarchist historian and archivist Max Nettlau.13 Danielewicz sent him the copies he had on hand from its San Diego and San Francisco runs. Some of these likely ended up with Nettlau’s papers in the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam, where they were digitized as the scans now being made available. The two also discussed a Los Angeles paper, The Cactus, run by a Carl Brown. Danielewicz told Nettlau to get in touch with the editor as he had no copies on hand.14

The Beacon was not the sole Anarchist outlet during its print run; many issues carried a listing of radical journals in several languages. A little over half were in the United States, including English, German, Yiddish, and Czech-language periodicals. Some, like Topeka’s Lucifer focused on radical free-love matters. Others, like St. Louis’ Die Parole, were surviving papers affiliated with the Black International since before Haymarket. London was home to several friendly English-language publications as well as a German and Yiddish newspaper. Even further afield were Paris’ La Revolte, Copenhagen’s Arbejderen, and El Perseguido in Buenos Aires.

!['The Beacon' Radical Journals listings for: Freedom (Cook Co. Il Chicago), Twentieth Century (New York), Lucifer (Topeka, KS), Egoism (San Francisco), Freethought (San Francisco), The Reasoner (New York), Chicago Liberal (Chicago), Freedom (London), The Anarchist Labor Leaf (London), The Commonwel (London), Freiheit (New York), Der Anarchist (St. Louis), Der Arme Teufel (Detroit), Die Parole (St. Louis), Die Autonomie (London), La Revolte (Paris), Volne Listy (New York), Der Arbeiter Freund (London), Freie Arbeiter Stimme (New York), Nedeln Hlas Lidu (care of Freiheit in New York), Tydni List Hlas Lidu (New York), El Persequido (Buenos Ayres [sic], Argentina), Arbejderen from (Kopenhagen, Denmark)](https://historicalseditions.noblogs.org/files/2022/04/Beacon-International-1024x972.png)

Scholarship in recent decades has painted a dynamic new picture of a globespanning, militantly-anti-capitalist and anti-colonial anarchist movement in the first decades of the 20th century.15 The Pacific Coast of North America became a hub for interconnected, interracial radical movements. European immigrants and us-born white radicals worked together with Japanese anarchists, Sikh and Bengali anti-colonial syndicalists, and Indigenous Mexican revolutionaries, all in a context where the mainstream labor movement thrived on the continuing racism of the earlier Red International. The Beacon is thus a key piece in the puzzle sorting out the development of these contrasting radicalisms.

Yet when investigating such connections over the course of a full-generation, it is important to emphasize the fairly milquetoast ‘anti-racism’ actually visible within The Beacon, both hinting at some of the weaknesses in this later coalition but also underselling its strengths. In its surviving issues, The Beacon gave no space to anti-Chinese rhetoric, a welcome contrast to deeply racist local counterparts run by other white socialists like the California Arbeiter-Zeitung edited by Paul Grottkau. But The Beacon in fact had nothing at all to say about Chinese people, positive or negative; it also did not survive long enough to voice an opinion on a renewed wave of Anti-Chinese agitation in 1892.

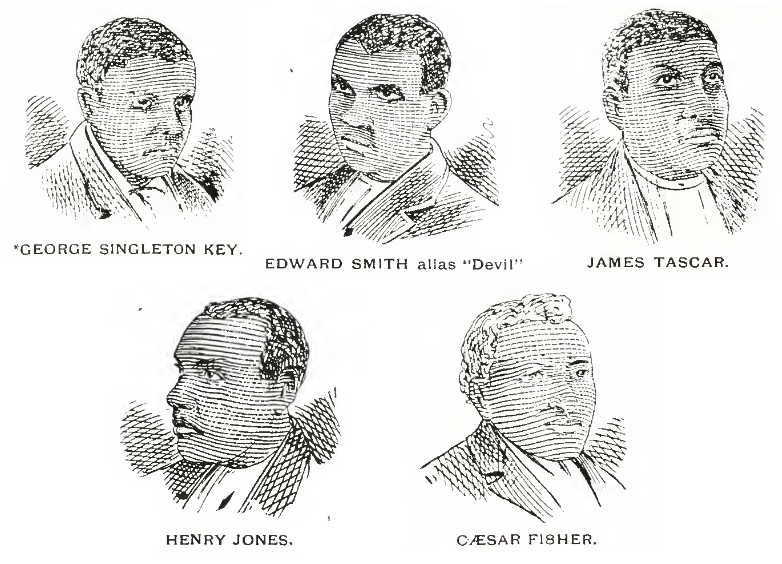

In a rare editorial discussing race-prejudice, “Wake Up, Ye Abolitionists!”, Danielewicz displays a sort-of anti-racist perspective discussing a case involving black men on the far side of the continent. It recounts the harrowing dilemma faced by a group of black workers from Baltimore recruited by a “Baltimore blood-sucker company” to dig for guano in the Caribbean.16 Righteously infuriated by rough and “poisonous” work conditions, “miserable” food and “shelter unfit for habitation,” the workers marched on the Superintendent demanding changes. The boss’:

Answer was the discharge of the contents of a rifle into one of the poor men’s face. This, of course aroused the feelings of indignance of these human beings and they at once resented the outrage by a general attack upon the official tyrants, one of whom was shot and killed. The balance of the dude-tyrants, fearing the just revenge of the outraged colored men, then fled to Baltimore upon a cruiser which had happened along.

The escaped managers got the government to kidnap the Black men from the stolen Haitian island of Navassa to Baltimore. There they were put on trial three separate times until all of the men were found guilty. To Danielewicz, that ‘triple jeopardy’ made “This is a case that has no equal in the history of what is termed civilization. It puts into the shade even that most dastardly crime this filthy government has every perpetrated, the foul murder of the martyrs Parsons, Spies, Fischer, Engel and Lingg, and the imprisonment of the heroes Fielden, Schwab, and Neebe.”

Yet even while rhetorically placing the plights of these black men from Baltimore above even that of the already globally-known Haymarket martyrs, Danielewicz was speaking to his mostly white audience of settler “American Anarchists.” He saw the case as illustrating frighteningly that slavery had not been abolished, but that a system of “chattleslavery” had been:

superseded by wageslavery; that the system of slavery is gone, yet the substance remains. Nor is it your colored brother alone who suffers. Your own race, your own color are victims as well. Look around you. Millions of your brothers and sisters; fathers, mothers, husbands, wives, from the gray and aged down to the tender child are wearing out their miserable existence and going down into untimely graves by the inhuman drudgery they are obliged to perform in workshops, factories, and mines…

Rise, then, those of you who still have the manhood and spirit of your noble ancestors, and ‘abolish,’ DESTROY this infernal machine-government – which has cursed the ages and makes slaves of your race.17

Settler radicals in abolitionist, feminist, and working-class circles “appropriating” the struggles faced by Black people in the US as a platform to about-facedly highlight and incite combat against their own oppression was not uncommon then. Frankly, it isn’t today. It was ultimately black mutual-aid organizations that took care of the Navassa rebels, with little apparent help from white radicals.

Given Danielewicz’s own messy background (to be detailed in future writing), this writer personally wishes to push against his posthumous valorization as “anti-racist icon.” White folks too often get credit in that realm. Danielewicz simply came to see the true horror in a demon he had helped to summon in the first place.

The selection of Beacon issues now available digitally makes it easier for researchers to make their own judgements on this and other matters.

1“An Amendment,” The Beacon, May 3, 1890. “Dissenting Voices,” The Beacon, May 24, 1890. “Grumblers,” The Beacon, May 31, 1890. Also May 3, 1890, included humorous editorial rebuttal below a submission by ‘Mono’ advocating for “education over dynamite”: ’“What a lot of ignorant, boisterous and unreasoning people! Want to use physical force to solve such a great problem! Peace, peace, peace! Agitation and education, that is the only way to accomplish anything!” said the squire to his companion, and helped himself to another glass of champagne and another slice of roast turkey’

2Vol 1 (1890), no. 12-3, 15-17 and Vol 2 (1891) no. 1-2, 6-8, 18 of The Beacon were available to the writer for digitization. Vol 2 (1891) no. 5, 9, 11, 12, 14, & 19 are available physically and in microfilm at the University of Michigan Labadie Collection and possibly some other libraries.

3“Cheering Voices,” The Beacon, May 24, 1890. “A Protest,” The Beacon, May 24, 1890.

4J. Wm. Lloyd, “Methods — Mental Resistance,” The Beacon, May 31, 1890.

5“Pointers,” Egoism, San Francisco, September, 1891.

6See for instance Dyer D. Lum, “Social Revolution,” “Les Septembriseurs,” The Beacon, May 3, 1890. Dyer D. Lum, “Reflections,” The Beacon, May 17 1890.

7Lucy Parsons, “Thoughts and Things,” The Beacon, January 31, 1891.

8Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Hurricaine.” The Beacon, April 26, 1890.

9“Cheering Voices,” The Beacon, April 26, 1890. “Cheering Voices,” The Beacon, May 3, 1890.

10“Mary Aikin – The First (Only!) Grinnell Woman Imprisoned for Causing an Abortion.” Grinnell Stories. http://grinnellstories.blogspot.com/2018/03/mary-aikinthe-first-grinnell-woman.html accessed January, 2022.

11See Alexander Saxton’s The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California, for an older account, more of this story tocome on this blog.

12Digitized issues of The Firebrand are available here: https://firebrandpdx.wordpress.com/firebrand-issues-1895-1897/ See also Alecia Jay Giombolini, “Anarchism on the Willamette: the Firebrand Newspaper and the Origins of a Culturally American Anarchist Movement, 1895-1898.”

13Letter from Sigismund Danielewicz to Max Nettlau. June 8, 1890. Max Nettlau Papers, International Institute for Social History. https://hdl.handle.net/10622/ARCH01001.2231

14Carl Browne seems to have run the Cactus as some sort of quasi-labor reform paper from 1888-90, available in a few California libraries. Later was affiliated with the People’s Party, writing an 1892 manifesto for it, as well as Coxey’s Army, and also published a periodical in Stockton, CA, Labor Knight.

15See for instance Maia Ramnath, Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire; David Struthers, The World in a City: Multiethnic Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century Los Angeles; Kenyon Zimmer, Immigrants Against the State: Yiddish and Italian Anarchism in America; ed. Christopher J. Castañeda and Montse Feu, Writing Revolution: Hispanic Anarchism in the United States.

16“Wake Up, Ye Abolitionists!” The Beacon. May 17, 1890.

17Ibid.