West Coast Historical Anarchist Media in Print and Online

Newspapers were first published under the black flag on the Pacific Coast over 130 years ago. Blogs, podcasts, and zine distros carry on that work today.

This incomplete list of digitized anarchist publications from the colonized west of the so-called united states makes accessible that long history of insurgent media. Anarchists seeking inspirations and warnings from the past will hopefully find it useful.

Newspapers and magazines from the late-19th and early 20th century chronicle everyday organizing and insurrectionary moments during an era when the West Coast was a major node in a globe-spanning anti-colonial, anti-capitalist anarchist movement. Papers published in several languages from Los Angeles to San Francisco, Portland to Home, Washington were backbones of local networks, sometimes attracting global attention. The various publications below are available in various formats, from PDFs of individual issues to searchable web tools.

There is a dearth of publications from the 1940s until the 1960s; not unexpected given the lull of anarchistic movements in these decades. The revival came in the form of independent and often diy bulletins and newsletters. The 70s witnessed a small proliferation of publications from clandestine prison papers to anarchist comic books to the birth of zine culture.

With the rise of the internet, Indymedia became an early hub building on connections established at the 1999 WTO in Seattle. A network of frequently anonymous, sometimes submission-driven anarchist blogs proliferated in the years that followed. Some of these blogs are still active today, but many old sites remain live and are valuable resources for the interested. There was also several anarchist magazines and newspapers published in Seattle and Tacoma during the late 2000s and 2010s with digitized copies available for reading.

There are undoubtedly publications missing from this list. Old periodicals become lost to time or collect dust in archives or on microfilm. Vibrant anonymous blogs become dead links, occasionally accessible in limited form on the Wayback Machine. One aim of Historical Seditions is to seek out and preserve these. More digitized historic newspapers will be added to our site in the future, and we are always on the hunt for forgotten URLs and PDFs. If you have leads to expand this list, contact us at historicalseditions [at] riseup [dot] net.

A growing, global list of digitized anarchist publications is available at lidiap.ficedl.info

Digitized by Historical Seditions

The Beacon

Kakumei/The Revolution

Free Society & The Firebrand

Storming Heaven

Enfant Terrible

Many more coming soon!

So-Called PNW

The Firebrand – Portland (Or.), 1895-1897

vol. 1, nos. 1, 8, 10, 12-15, 17-22, 24-25, 27-47, 49-52

vol. 2, nos. 2-8, 10-16, 18-19, 21-24, 27, 30-32, 34-52

vol. 3, nos. 1-34

vol. 1, nos. 1, 42

vol. 2, nos. 31-32, 34-45, 47-52

vol. 3, nos. 1-34

Mirror reduced

Discontent – Home (Wash.), 1898-1902

vol. 1, nos. 5, 10, 27, 38, 43, 45, 49-50

vol. 2, nos. 2, 5, 7, 10-14, 43, 48-52

vol. 3, nos. 2-12, 14-20, 22-23, 25-28, 30-43, 46-52

vol. 4, nos. 2-4, 6-13, 15-19, 21-23, 25-31

Clothed with the Sun – Home (Wash.), 1900-1904

vol. 3, nos. 3, 10

vol. 1, nos. 2-3, 10-12

vol. 2, nos. 1-12

vol. 3, nos. 1,3,10

The Demonstrator – Home (Wash.), 1903-1908?

vol. 1, nos. 1-25, 27-31

nos. 1-142

The Industrial Worker – Spokane, Seattle, 1909-1931

vol. 1 – vol. 5

The Agitator – Home (Wash.), 1910-1912

Complete Set

Hammerslag – Seattle, 1911-1912

nos. 1-2, 4

Why? – Tacoma, 1913-1914

Complete Set

Mirror

Mirror

The Dawn – Seattle, 1922-?

vol. 1 nos. 1-8

The Seattle Group Bulletins – Seattle, 1965-1971

no. 1-60 text only

Original Scans

Lilith – Seattle, 1968-1970

nos. 1-3

Earth and Fire – Vancouver, 1972

nos. 1, 2

Revolutionary Anarchist – 1973-?

no. 3

Open Road – Vancouver, 1976-1990

Complete Set

Mirror

Anarchist Black Dragon – Walla Walla, 1978-1983

nos. 2-6, special issue, 8-11

British Columbia’s blackout – Vancouver, 1978-1984?

nos. 1-4, 6, 66, 74-75, 77, 79, 82-85, 91, 109, 117

The Spark: A Newsletter of Contemporary Anarchist Thought – Port Townsend, 1982-1984

nos. 1-5

Ecomedia – Vancouver, 1988-1991?

nos. 1-2, 4-6

nos. 12-21, 23-39, 41-51, 54-69, 72-76, 78-81, 83, 85, 87-92, 94-100

The Insurgent – Eugene, 1991-Present

2010-present issues

New World Disorder – Tacoma, 1992

no. 1

Spontaneous Combustion – Seattle and Portland, 1992

no. 1

NWAC Northwest Anarchist Collective – Seattle, 1992-1993?

nos. 1-2

Anti-Power – Seattle, 1993

no. 1

Black Autonomy: A Journal of Anarchism and Black Revolution – 1994-1997

v. 1 nos. 1-5

v. 2 no. 5

v. 3 nos. 1, 3-5

Crimethinc – Olympia and Elsewhere, 1996-Present

Legacy Article Search: crimethinc.com/library

Parascope – Seattle, 1999?-2000?

no. 4

Indymedia – Seattle, 1999-2013 Portland, 2000-2020

Seattle Wayback Machine

Portland Wayback Machine

Green Anarchy – Eugene, 2000-2008

nos. 5, 7

nos. 6-25

Face to Face with the Enemy – Vancouver, 2004-2007?

facetofacewiththeenemy.wordpress.com

Rad Dad – Portland, 2005-2013

no. 20

Unfinished Business – Portland, 2005

no. 3

A Murder of Crows – Seattle, 2006-2007

nos. 1-2

Prisoner’s Dillema – Seattle, 2006-?

no. 1

CrimethInc. Worker Bulletin – Olympia, 2007

no. 47

no. 47/74

Wii’nimkiikaa – 2007-2010

wiinimkiikaa.wordpress.com

Aint No Party Like a West Coast Party – Olympia, 2008

no. 1

Intersections – Portland and Tacoma, 2008-2009

nos. 1, 4, 5

Pink and Black Attack – Olympia, 2008-2010

nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Vancouver Anarchist Online Archive – Vancouver, 2009-2010

vanarchive.wordpress.com

The Rebel – Tacoma, 2009

no. 1

Autonomy//253 – Tacoma, 2010-2011

autonomy253.wordpress.com

Magazine Issue 3

nos. 1-5

Lunaria Press – Tacoma, 2010-2011

lunariapress.blogspot.com

Unmanageable Outlaws – 2010-2011

amiableoutlaws.wordpress.com

Continual War – 2010-2012

2010-2011 continualwar.wordpress.com

2011-2012 continwar.noblogs.org

Autonomy Acres – Rural PNW, 2010-2015

autonomyacres.wordpress.com

Tides of Flame – Seattle, 2011-2012

Complete Set

Puget Sound Anarchists – 2011-Present

PugetSoundAnarchists.org (Current Site, 2014-Present)

Wayback Machine (2011-2013)

Warrior Publications – Occupied Coast Salish Territory, Vancouver BC, 2011-Present

warriorpublications.wordpress.com

Gray Coast – Pacific Northwest, 2011-2013

greycoast.wordpress.com

Portland Occupier – Portland, 2011-Present

portlandoccupier.org

BCBlackOut – So-Called British Columbia, 2011-Present

bcblackout.wordpress.com

(A) Wild Harbor – Aberdeen, 2012

awildharbor.wordpress.com

Seattle Free Press – Seattle, 2012-2015

Wayback Machine (2012-2015)

Anarres Press – Seattle, 2013-2015?

anarrespress.wordpress.com

Storming Heaven – Seattle, 2013-2015

nos. 2-6

Warzone Distro – Chicago, Portland, elsewhere – 2013 – Present

warzonedistro.noblogs.org

Outside Agitator (206) – Seattle, 2015-2016

nos. 1-2

Blog Wayback Machine (2015-2016)

Black and Green Review – Salem, 2015-2018

no. 1

The Transmetropolitan Review – Seattle, 2015-2018 (Magazine), 2015-Present (Blog)

nos. 1-6, 7, 8

thetransmetropolitanreview.wordpress.com

Wreck – Vancouver, 2015-2016

Complete Set

Salish Sea Black Autonomists – Olympia, 2017-2020

blackautonomynetwork.noblogs.org

1312press – Seattle, 2018?-Present

Published Zines – 1312press.noblogs.org/1312-published-titles

Rose City Counter-Info – Portland, 2020-Present

rosecitycounterinfo.noblogs.org/

PNW Youth Liberation Front – 2020-2021

pnwylf.noblogs.org/

youthliberation.noblogs.org/

no more city – Vancouver, 2020-2022

2020-20201 Issues – nomore.city/archive

Fugitive Distro – Olympia, 2021-Present

autistici.org/fugitivedistro

Rose City Radical – Portland, 2021-2022

nos. 1-4 rosecityradical.com/past-issues

Sabot Media – Aberdeen, 2021-Present

Blog

Black Cat Distro Zines

The Communique Newsletter nos. 1-3

Creeker – Fairy Creek, Vancouver Island, 2021-Present

vol. 1-4

BC Counter-Information – so-called British Columbia, 2022-Present

bccounterinfo.org

The Occupied West

The Beacon – San Francisco, 1889-1891

vol. 1, nos. 12-13, 15-17

vol. 2, nos. 1-2, 6-8, 18

Egoism – San Francisco, 1890-1897

vol. 1

vol. 2

vol. 3, nos. 1, 18, 23

vol. 4, nos 1-2

Enfant Terrible – San Francisco, 1891-92

nos. 3, 6

Secolo Nuovo – San Francisco, 1894-1906

vol. 7 no. 17

vol. 9 no. 26

Free Society (Sucessor of Portland’s The Firebrand) – San Francisco/Chicago, 1897-1904

vol. 4, no. 1

vol. 5, nos. 31, 34-35, 39-41, 48

vol. 6, nos. 7-21, 24-26, 28-33, 35-58

vol. 7, nos. 1-3, 5, 8, 14-15, 31, 36

vol. 9, nos. 1-52

vol. 10, nos. 19-20, 33, 38, 42, 52

vol. 10b, nos. 1-3, 7-8

Mirror vol. 9

vol. 10, no. 20

Regeneración – Los Angeles and elsewhere, 1900-1901, 1904-1906, 1910-1918

Complete Set

La Protesta Umana – San Francisco and Chicago, 1900-1905

1902-1903

Kakumei/The Revolution – Berkeley, 1906-1907

no. 1

Revolución – Los Angeles, 1907-1908

nos. 1-4, 6-11, 13-17, 19-29

Regeneración. Sezione Italiana – Los Angeles, 1911

Complete Set

Hindustan Ghadar – San Francisco, 1913-192?

Assorted 1913-1917 issues

The Blast – San Francisco, 1916-1917

Complete Set

Man! – San Francisco, 1933-1940

vol. 3, no. 7/8

Now & After – San Francisco, 1977-1978

no. 1

Anarchy Comics – San Francisco, 1978-1987

Complete Set

Slingshot – Berkeley, 1988-Present

nos. 58-137

Anarchist Labor Bulletin – San Francisco (Calif.), 1989?-1990?

nos. 18-19

Willful Disobedience – Los Angeles, 1996-2006

vol. 3, no. 5

vol. 5, nos. 1-2

Ignite! – Denver, 2011-2012

Complete Set

Black Flag – Los Angeles, 2012-2016

Complete Set

Black Seed – Berkeley, 2014 – Present

nos. 1-6

It’s Going Down – Bay Area and Elsewhere, 2015-Present

itsgoingdown.org

2015/Old Legacy Articles via Wayback Machine

Winter-Spring 2016 Print Compilation

Spring 2017 Print Compilation

Before the internet wove its globe-spanning web of social media, far-flung groups and individuals were brought together via the print culture of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and journals. The revolutionary culture of the anarchist movement was, in many respects, incubated in the pages of its printed matter. Letters to ones favorite paper often engaged in discourse with one another, bringing correspondents from San Francisco to South Africa to the same playing field. The rapid proliferation and decreasing cost of such publications thus provided more than just a passive window through which to view the world, opening up a new intellectual and social universe.

Before the internet wove its globe-spanning web of social media, far-flung groups and individuals were brought together via the print culture of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and journals. The revolutionary culture of the anarchist movement was, in many respects, incubated in the pages of its printed matter. Letters to ones favorite paper often engaged in discourse with one another, bringing correspondents from San Francisco to South Africa to the same playing field. The rapid proliferation and decreasing cost of such publications thus provided more than just a passive window through which to view the world, opening up a new intellectual and social universe. But when she turned 17 (the age of confirmation in her church), Clara instead “stood up and announced that, having lost her belief in the tenants of the church, she was renouncing her membership.

But when she turned 17 (the age of confirmation in her church), Clara instead “stood up and announced that, having lost her belief in the tenants of the church, she was renouncing her membership.

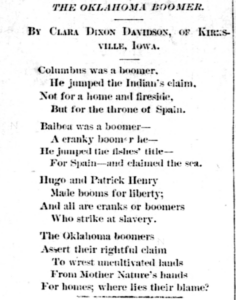

Clara’s poem put a bottom-up spin on the issue, seemingly arguing that settler’s were even more justified in making claims than conquistadors had been; the latter did so on behalf of a crown, the former to find land for homes.

Clara’s poem put a bottom-up spin on the issue, seemingly arguing that settler’s were even more justified in making claims than conquistadors had been; the latter did so on behalf of a crown, the former to find land for homes. In 1884, letters and poems from Clara appear in Chicago’s Alarm, the English weekly of the “Black” IWPA, as well as the main organs of the IWA, Denver’s Labor Enquirer and San Francisco Truth. By this time Clara clearly counted herself in the radical camp, ending a treatise in the Enquirer advocating for men and women to organize with the famous call:

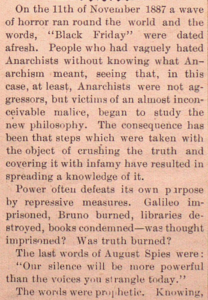

In 1884, letters and poems from Clara appear in Chicago’s Alarm, the English weekly of the “Black” IWPA, as well as the main organs of the IWA, Denver’s Labor Enquirer and San Francisco Truth. By this time Clara clearly counted herself in the radical camp, ending a treatise in the Enquirer advocating for men and women to organize with the famous call: In May, 1886, hundreds of thousands struck demanding the Eight Hour Day across much of the United States. IWPA sections played a significant agitational role in the uprising that witnessed intense clashes between strikers and armed state forces. Most infamously, police murdered several workers outside the McCormick harvester factory in Chicago. Local anarchists responded by calling a mass-meeting at “The Haymarket.”

In May, 1886, hundreds of thousands struck demanding the Eight Hour Day across much of the United States. IWPA sections played a significant agitational role in the uprising that witnessed intense clashes between strikers and armed state forces. Most infamously, police murdered several workers outside the McCormick harvester factory in Chicago. Local anarchists responded by calling a mass-meeting at “The Haymarket.” One of the very few opponents was Sigismund Danielewicz, a tireless traveling organizer. Sigismund was the Red International’s Secretary until he spoke out against the anti-Chinese violence, calling for a move to higher principles.

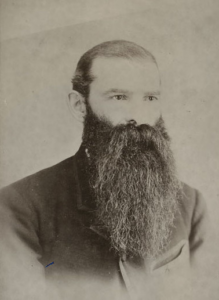

One of the very few opponents was Sigismund Danielewicz, a tireless traveling organizer. Sigismund was the Red International’s Secretary until he spoke out against the anti-Chinese violence, calling for a move to higher principles. Clara was drawn to San Francisco’s bohemian literary milieu, and her articles and poems from the following decades appear frequently in publications from the Overland Monthly to The Nation. But Clara didn’t rely solely on the good grace of other editors to publish her work.

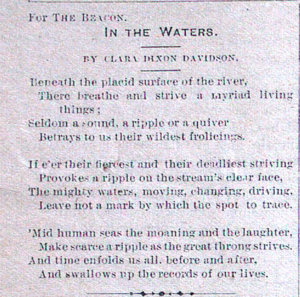

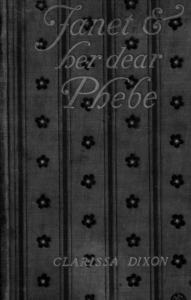

Clara was drawn to San Francisco’s bohemian literary milieu, and her articles and poems from the following decades appear frequently in publications from the Overland Monthly to The Nation. But Clara didn’t rely solely on the good grace of other editors to publish her work.

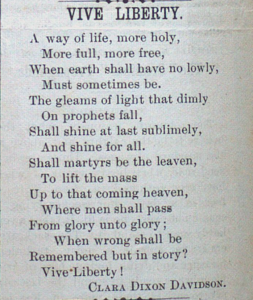

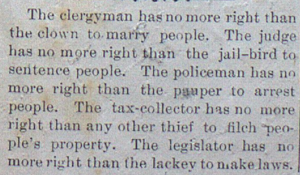

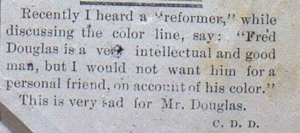

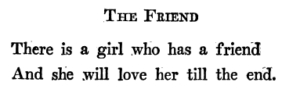

Both surviving issues of Enfant Terrible lead with a poem by Clara before alternating between long sections written by Clara and Harry. Reading from a 21st century vantage it comes off almost like a radical couples blog. Short fables and clever little anecdotes provoke little mental challenges to authority or expose societal hypocrisy. Brief commentary on current events like a proposed law closing business on Sunday reveals Clara and Henry’s distaste for intertwined capital, government, and organized religion.

Both surviving issues of Enfant Terrible lead with a poem by Clara before alternating between long sections written by Clara and Harry. Reading from a 21st century vantage it comes off almost like a radical couples blog. Short fables and clever little anecdotes provoke little mental challenges to authority or expose societal hypocrisy. Brief commentary on current events like a proposed law closing business on Sunday reveals Clara and Henry’s distaste for intertwined capital, government, and organized religion. Enfant Terrible was relatively short-lived, its last available issue on December 20, 1891 was only the 6th. The February issue of another local individualist anarchist paper, Egoism, announced its cessation and that subscribers would receive their paper. Egoism’s May issue noted the couple’s participation in debates at the “People’s Free Lyceum” over the meaning of “Philosophical Anarchy.” Henry argued that “majority rule is inexpedient and a social failure because it defeats equal freedom, whereupon it follows that Anarchism is the correct social principle.” Clara delivered her own “sharp hits.”

Enfant Terrible was relatively short-lived, its last available issue on December 20, 1891 was only the 6th. The February issue of another local individualist anarchist paper, Egoism, announced its cessation and that subscribers would receive their paper. Egoism’s May issue noted the couple’s participation in debates at the “People’s Free Lyceum” over the meaning of “Philosophical Anarchy.” Henry argued that “majority rule is inexpedient and a social failure because it defeats equal freedom, whereupon it follows that Anarchism is the correct social principle.” Clara delivered her own “sharp hits.” Henry Dixon Cowell was born March 11, 1897; Clara was 46 years old.

Henry Dixon Cowell was born March 11, 1897; Clara was 46 years old.

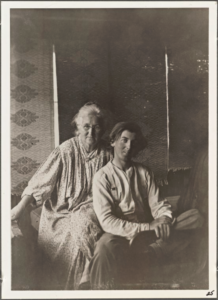

Ellen entered into a tight relationship with the mother-son duo, moving them into her house and later making Henry something of an adopted son and executor of her will. She also helped Henry make musical connections and afford a Steinway piano.

Ellen entered into a tight relationship with the mother-son duo, moving them into her house and later making Henry something of an adopted son and executor of her will. She also helped Henry make musical connections and afford a Steinway piano.

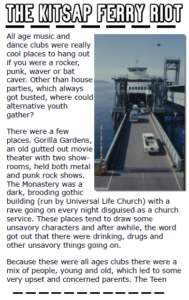

The Kitsap Ferry Riot tells the story of the restrictive old Seattle Teen Dance Ordinance and a punk riot that occurred on the ferry from Bremerton as a result. The text is pulled from the defunct website of a documentary about the riot by Chris Loomey,

The Kitsap Ferry Riot tells the story of the restrictive old Seattle Teen Dance Ordinance and a punk riot that occurred on the ferry from Bremerton as a result. The text is pulled from the defunct website of a documentary about the riot by Chris Loomey,  The Eyes of a Monster is the tale of Chris Monfort. Appalled by police brutality in his community, Chris looked the monster in the eye and refused to blink. He launched a one-man war against Seattle Police in 2009, bombing vehicles and killing one SPD officer in an ambush. Chris mysteriously died in Walla Walla State Penitentiary in 2017. (3 sheets letter)

The Eyes of a Monster is the tale of Chris Monfort. Appalled by police brutality in his community, Chris looked the monster in the eye and refused to blink. He launched a one-man war against Seattle Police in 2009, bombing vehicles and killing one SPD officer in an ambush. Chris mysteriously died in Walla Walla State Penitentiary in 2017. (3 sheets letter) 1856: The Battle in Seattle is the tale of Chief Leschi, the Nisqually, and other warriors who fought to expel the settler-colonial leviathan in its infancy. (2 sheets letter)

1856: The Battle in Seattle is the tale of Chief Leschi, the Nisqually, and other warriors who fought to expel the settler-colonial leviathan in its infancy. (2 sheets letter) Anarchists and Rebellion in Walla Walla State Prison is an account of the Anarchist Black Dragon, an imprisoned anarchist collective who published an underground newspaper and helped spur several prisoner uprisings. (1 sheet letter)

Anarchists and Rebellion in Walla Walla State Prison is an account of the Anarchist Black Dragon, an imprisoned anarchist collective who published an underground newspaper and helped spur several prisoner uprisings. (1 sheet letter) The Centralia IWW tells of the lumberjacks and hobos who organized a revolutionary union in this small Washington town. The intense repression they faced culminated in the so-called Centralia Tragedy in 1919. (2 sheets letter)

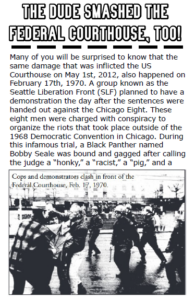

The Centralia IWW tells of the lumberjacks and hobos who organized a revolutionary union in this small Washington town. The intense repression they faced culminated in the so-called Centralia Tragedy in 1919. (2 sheets letter) The Dude Smashed the Federal Courthouse, Too! recalls the nationwide uprising in 1970 over the trial of Black Panther Bobby Seale and the Chicago Seven. The rowdiest solidarity action occurred in Seattle, where the federal courthouse was smashed. One of the most famous arrestees was Jeff Dowd, inspiration for “The Dude” in “The Big Lebowski” (1 sheet letter)

The Dude Smashed the Federal Courthouse, Too! recalls the nationwide uprising in 1970 over the trial of Black Panther Bobby Seale and the Chicago Seven. The rowdiest solidarity action occurred in Seattle, where the federal courthouse was smashed. One of the most famous arrestees was Jeff Dowd, inspiration for “The Dude” in “The Big Lebowski” (1 sheet letter)